Lifting the Corporate Veil: Doctrine, Evolution, and Judicial Trends under the Indian Companies Act, 2013

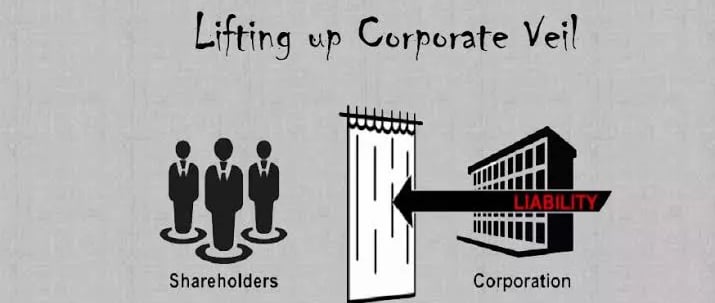

One of the most fundamental principles in corporate law is that a company is a separate legal entity. This concept—solidified in Salomon v. Salomon & Co. Ltd.—allows companies to enjoy rights like limited liability, perpetual succession, and legal personhood. In simple terms, once incorporated, a company is no longer just an extension of its founders or shareholders; it stands on its own. But with great power comes the potential for misuse. When corporate structures are used to commit fraud, evade taxes, or conceal illegal activities, courts may choose to pierce this legal shield—what’s commonly referred to as “lifting the corporate veil.” This doctrine enables courts to look beyond the company façade and hold the real actors accountable.

Chow Ananda Mungyak, 3rd Year BA. LLB(Hons.)

4/22/20253 min read

In this blog post, we unpack the origin, development, and judicial interpretation of this powerful legal tool, with a focus on the Indian context post the Companies Act, 2013.

The Foundation: Corporate Personality & the Separate Legal Entity

The landmark case of Salomon v. A. Salomon & Co. Ltd. (1897) is where it all began. The House of Lords held that a duly registered company is a legal person, distinct from its shareholders—even if it is fully controlled by one.

This paved the way for limited liability, which protects investors and encourages entrepreneurship. It also gave rise to complex corporate structures, multinationals, and joint ventures. But it also created a loophole—bad actors could hide behind the corporate mask to dodge accountability.

Enter the doctrine of veil lifting.

The Evolution: From UK Origins to Indian Jurisprudence

The UK courts, while generally cautious, recognized early on that the corporate form can be manipulated. In cases like:

• Gilford Motor Co. v. Horne (1933) – A former employee used a company to dodge a non-compete clause.

• Jones v. Lipman (1962) – A man formed a company to avoid a court order on a land sale.

These cases marked a shift: when companies are used as “masks” to hide misconduct, courts are willing to tear the veil apart.

In India, the doctrine was inherited from British law, and post-independence, courts began tailoring it to Indian realities—especially in matters involving public interest, tax evasion, and state accountability.

Companies Act, 2013: A Statutory Perspective

Though primarily a judicial doctrine, certain provisions in the Companies Act, 2013 give statutory backing to veil lifting:

• Section 339: Personal liability for fraudulent conduct of business (especially during winding-up).

• Section 447: Penalties for fraud.

• Section 2(60): Definition of “officer in default”—useful in identifying responsible individuals.

These provisions enable courts and tribunals to hold promoters, directors, and shadow controllers accountable for wrongdoings that would otherwise be insulated by the company’s legal personality.

Indian Judicial Trends: Selective Yet Expansive

Indian courts have developed a rich body of jurisprudence around veil lifting. Some key cases include:

• Delhi Development Authority v. Skipper Construction (1996)

→ Veil lifted to protect defrauded homebuyers.

• Gotan Lime Stone Case (2016)

→ Examined ownership to detect regulatory abuse in a mining lease.

• Kapila Hingorani v. State of Bihar (2003)

→ Treated state-run corporations as extensions of the State to enforce workers’ rights.

• Vodafone International Holdings v. Union of India (2012)

→ Refused to lift the veil, drawing a line between legitimate tax planning and evasion.

Indian courts tread a fine line—balancing corporate freedom with the imperative of justice.

Comparative Lens: UK vs USA vs India

• UK: Conservative approach. In Prest v. Petrodel (2013), the UK Supreme Court reiterated that veil lifting is a last resort, used only to prevent evasion of legal duties.

• USA: More liberal. Courts consider whether there’s a unity of interest between the corporation and its owners (under-capitalization, commingling of funds, etc.).

• India: Middle ground. While leaning toward the UK’s cautious style, Indian courts have expanded veil lifting into areas like constitutional morality, public interest, and social justice.

🏛️ Modern Trends: SEBI, IBC & GAAR

The regulatory ecosystem in India has increasingly supported veil lifting in newer domains:

• SEBI Regulations

→ Used to tackle shell companies, proxy ownership, and disclosure violations.

• Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC)

→ Sections 66 and 69 hold directors personally liable for fraudulent conduct during insolvency.

• Tax Law & GAAR

→ While Vodafone upheld lawful tax planning, GAAR (General Anti-Avoidance Rule) equips authorities to ignore abusive corporate arrangements.

The Grey Areas: Need for Clarity

While powerful, the doctrine is not without flaws in the Indian context:

• Unpredictability: Judicial discretion without a codified test often leads to inconsistent decisions.

• Risk of Overreach: In PILs or public interest cases, courts may stretch the doctrine too far.

• Regulatory Overlap: Different authorities (NCLT, SEBI, IT Dept.) apply veil lifting differently.

India needs a balanced, codified framework—perhaps under the Companies Act or SEBI guidelines—to standardize when and how veil lifting should be used.

Conclusion: Toward a Just and Transparent Corporate Ecosystem

The corporate veil is not an impenetrable shield—it was never meant to be. As India’s economy becomes more complex and globalized, the need for corporate accountability is more pressing than ever.

Lifting the corporate veil remains a critical tool in the legal arsenal—one that ensures justice is served when the corporate form is misused.

Going forward, aligning judicial principles with regulatory clarity will help India strike the right balance between protecting corporate autonomy and preventing abuse.

Because Every Legal Mind Deserves a Great Conversation.

Legaltea.in@gmail.com

+91 6284295492

MSME Certified

© 2025 Legal Tea. All rights reserved.