The Doctrine of Indoor Management: How It Protects People Doing Business with Companies

When you’re dealing with a company — maybe signing a contract or entering into a partnership — you probably assume everything is in order internally, right? You wouldn’t expect to doublecheck if the board approved it, whether a resolution was passed, or if internal protocols were followed. That’s where the Doctrine of Indoor Management comes in. It acts like a legal safety net for people dealing with companies from the outside.

Parikshit Sharma, 3rd year, BB.A; LL.B

4/25/20253 min read

The idea is simple: if everything looks fine on the surface, you’re allowed to trust it — unless something seems obviously wrong. This doctrine is built on principles of fairness and practicality, especially given how complex internal company processes can be. It helps maintain smooth business operations by reducing unnecessary hurdles for outsiders.

Breaking It Down: What Is the Doctrine of Indoor Management?

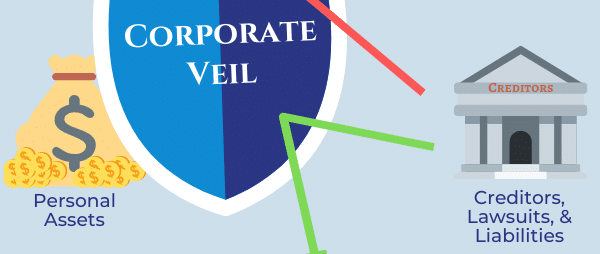

The Doctrine of Indoor Management is basically a counterbalance to something called the Doctrine of Constructive Notice. Now, the Doctrine of Constructive Notice says that people dealing with a company are expected to be aware of its publicly available documents — like its Memorandum of Association or Articles of Association — because these are registered and accessible through the Registrar of Companies.

But here’s the catch: while you’re expected to know what a company is allowed to do (from its public documents), you’re not expected to know how it does it internally. And that’s exactly what the Doctrine of Indoor Management protects — it stops outsiders from being unfairly penalised just because something wasn’t followed properly inside the company.

How It All Started: The Landmark Case

This doctrine has its roots in an old but important English case: Royal British Bank v. Turquand (1856). In that case, the directors of a company borrowed money but hadn’t technically followed internal procedures. The court still sided with the lender, saying they had no way of knowing about the missing approval. That decision gave birth to the “Turquand Rule,” which forms the basis of the Doctrine of Indoor Management.

Indian courts later echoed the same principle. In Lakshmi Ratan Cotton Mills Co. Ltd. v. J.K. Jute Mills Co. Ltd. (1957), the court made it clear: if you’re dealing with a company in good faith, you don’t need to investigate its internal paperwork — unless there are obvious warning signs.

When Does This Doctrine Apply?

There are a few things that need to line up for this doctrine to work in someone’s favour:

1. Apparent Authority:

You must be dealing with someone who seems to have the authority to act on the company’s behalf.

2. No Knowledge of Irregularity:

You shouldn’t be aware — directly or indirectly — that something’s off inside the company.

3. Transaction Doesn’t Raise Red Flags:

If something about the deal feels suspicious, you're expected to dig a little deeper.

But It's Not Foolproof: The Exceptions

The doctrine doesn’t offer blanket protection. There are clear exceptions where it won’t help:

1. You Knew Something Was Wrong:

If you were aware that internal rules weren’t followed, you can’t hide behind this doctrine.

2. You Ignored Warning Signs:

If the situation seemed sketchy and you didn’t ask questions, that’s on you.

3. Forgery or Ultra Vires Acts:

If a document was forged or if the act goes beyond what the company is legally allowed to do (ultra vires), the doctrine won’t protect you.

Why It’s Still Relevant — Especially Today

With companies increasingly operating online, the way business is conducted has changed — but the doctrine is still super relevant. In fact, it’s more important now than ever.

Imagine this: A company official emails you a digitally signed agreement. Are you supposed to hack into their internal system to check if the board approved it? Of course not. That’s where this doctrine becomes a lifesaver. It lets you trust that internal processes were followed — unless there’s something obviously suspicious.

Today, most public documents (like incorporation details or Articles of Association) are available on portals like the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA). But internal approvals? Those might be stored on cloud drives, in password-protected folders, or logged during virtual meetings — completely out of reach for third parties.

This is why the doctrine is so valuable. It offers confidence to outsiders engaging in digital contracts, email communications, and online deals. However, this trust doesn’t mean recklessness — if something about the digital interaction feels shady (like an odd sender email or unexpected file), you’re still expected to act sensibly and verify.

Wrapping Up: Why You Should Care

The Doctrine of Indoor Management is all about protecting fair, honest dealings. It ensures that business interactions aren’t bogged down by red tape and gives outsiders the confidence to engage with companies without needing to be corporate detectives.

It strikes a smart legal balance — while you're expected to check public documents, you're not required to peek behind the curtain at every board meeting or internal memo. Especially in today’s fast-paced, digital business world, the doctrine keeps trust alive and transactions efficient.

Understanding this principle isn’t just important for law students or corporate lawyers — it’s useful for anyone who interacts with businesses, whether you’re signing a contract, negotiating a deal, or just trying to understand your rights.

References

Doctrine of Indoor Management – LawBhoomi

A Study on the Doctrine of Indoor Management and Its Exceptions – Lawyers Club India

Case Study: Royal British Bank v. Turquand (1856) – Legal Wires

Royal British Bank v. Turquand (1856) Case Summary – Legal Vidhiya

Commentary on Lakshmi Ratan Cotton Mills Co. Ltd. v. J.K. Jute Mills Co. Ltd. – Case Mine

Doctrine of Indoor Management – Legal Service India

Because Every Legal Mind Deserves a Great Conversation.

Legaltea.in@gmail.com

+91 6284295492

MSME Certified

© 2025 Legal Tea. All rights reserved.