Unraveling the Corporate Veil: Balancing Transparency and Internal Harmony

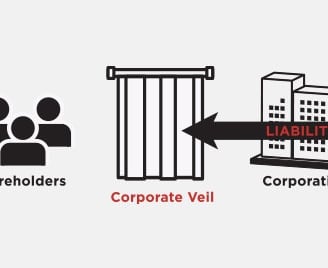

Navigating the intricate landscape of company law requires a keen understanding of how companies interact with the outside world and manage their internal affairs. Two fundamental doctrines, the doctrine of constructive notice and the doctrine of indoor management (also known as the rule in Royal British Bank v Turquand), play pivotal roles in shaping these interactions. While seemingly distinct, these doctrines represent two sides of the same coin, striving to balance the need for transparency with the facilitation of smooth internal operations.

Anopaishe Violet Maposa, 3rd Year BA. LLB(Hons.)

4/22/20253 min read

The Doctrine of Constructive Notice: A Public Declaration

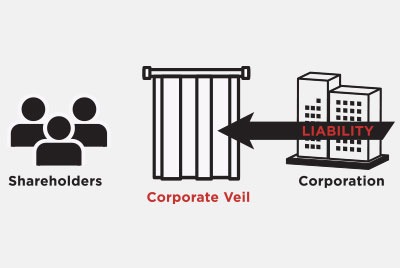

Imagine a company's memorandum and articles of association as its public constitution, filed diligently with the Registrar of Companies. The doctrine of constructive notice operates on the premise that once these documents are publicly registered, everyone dealing with the company is deemed to have knowledge of their contents. This is regardless of whether they have actually read or understood them.

This legal fiction serves a crucial purpose: it protects the company against outsiders who enter into transactions that are beyond the scope of its powers (ultra vires) or inconsistent with the limitations outlined in its constitutional documents. For instance, if the articles of association clearly state that the managing director can only borrow up to ₹1,00,000 without board approval, a lender providing a loan exceeding this amount cannot later claim ignorance of this limitation. The law presumes they had constructive notice of this clause.

However, the doctrine has been criticized for its unrealistic assumption that every individual or entity engaging with a company possesses detailed knowledge of its registered documents. In an era of increasing business complexity and voluminous filings, this presumption can lead to unfair outcomes for unsuspecting third parties.

The Doctrine of Indoor Management: Protecting the Outsider

In stark contrast to the outward focus of constructive notice, the doctrine of indoor management addresses the internal workings of a company. Stemming from the landmark case of Royal British Bank v Turquand (1856), this doctrine provides a shield for external parties dealing with a company in good faith.

The core principle is that an outsider is entitled to assume that the internal procedures and processes of the company have been duly complied with, as long as the transaction is within the company's powers. They are not bound to inquire into the regularity of internal management.

Consider a scenario where the articles of association require board approval for the transfer of certain assets. If a company director, seemingly acting with authority, enters into an agreement to sell these assets without obtaining the necessary board resolution, the third party acting in good faith is not prejudiced. They can assume that the internal approval process has been followed. The company cannot later repudiate the contract by claiming a lack of internal authorization.

The doctrine of indoor management is crucial for facilitating trade and commerce. It prevents companies from escaping their contractual obligations by citing irregularities in their internal affairs that are beyond the knowledge of external parties.

Balancing the Scales: Exceptions to the Rule

While the doctrine of indoor management offers significant protection to outsiders, it is not absolute.

Several exceptions limit its application:

❖ Knowledge of Irregularity:

If the outsider had actual or constructive notice of the internal irregularity, they cannot claim the protection of the doctrine.

❖ Suspicion of Irregularity:

If the circumstances surrounding the transaction were such that a reasonable person would have been put on inquiry, the outsider cannot blindly assume regularity.

❖ Forgery:

The doctrine does not apply where the transaction is based on a forged document, as forgery vitiates the entire transaction from its inception.

❖ Acts Outside Apparent Authority:

If the officer acting on behalf of the company lacks the apparent authority to enter into the transaction, the outsider cannot rely on the doctrine.

Conclusion: Fostering Trust and Efficiency

The doctrines of constructive notice and indoor management, though seemingly opposed, work in tandem to create a framework for regulating the interactions between companies and the external world. Constructive notice aims to ensure a degree of transparency regarding a company's powers and limitations, while the doctrine of indoor management fosters trust and efficiency in business dealings by protecting innocent third parties from the intricacies of internal company procedures.

Understanding the nuances of these doctrines and their exceptions is paramount for anyone engaging with a company, ensuring a balance between due diligence and the smooth flow of commerce.

References:

* Royal British Bank v Turquand (1856) 6 E&B 327

* Companies Act, 2013 (India) - Relevant sections pertaining to registration of documents and powers of the board.

* Gower and Davies' Principles of Modern Company Law.

* Ramaiya, A Guide to the Companies Act.

* Taxmann's Company Law.

Because Every Legal Mind Deserves a Great Conversation.

Legaltea.in@gmail.com

+91 6284295492

MSME Certified

© 2025 Legal Tea. All rights reserved.